Understanding Gain Bandwidth Product (GBW): What It Really Means for Op-Amp Design and Selection

In op-amp design, few specifications cause more confusion than Gain Bandwidth Product (GBW).

It looks simple. It sounds powerful. Yet it is often misused.

GBW is not a bonus feature.

It is a hard limit.

As the old engineering saying goes:

“You can’t get something for nothing.” — attributed to classical control theory texts

This article explains what GBW really means, why it matters, and how to use it correctly in real designs—without myths, shortcuts, or guesswork.

1. What Is Gain Bandwidth Product (GBW)?

Gain Bandwidth Product (GBW) is the product of an op-amp’s closed-loop gain and its usable bandwidth.

Core definition

[

\text{GBW} = \text{Gain} \times \text{Bandwidth}

]

If an op-amp has:

- GBW = 10 MHz

- Closed-loop gain = 10

Then the bandwidth is:

- 1 MHz

Why GBW is a trade-off

GBW describes a conservation law.

When gain goes up, bandwidth goes down. Always.

GBW does not mean:

- Faster response

- Better signal quality

- More accuracy by default

It only tells you how much frequency range remains after gain is applied.

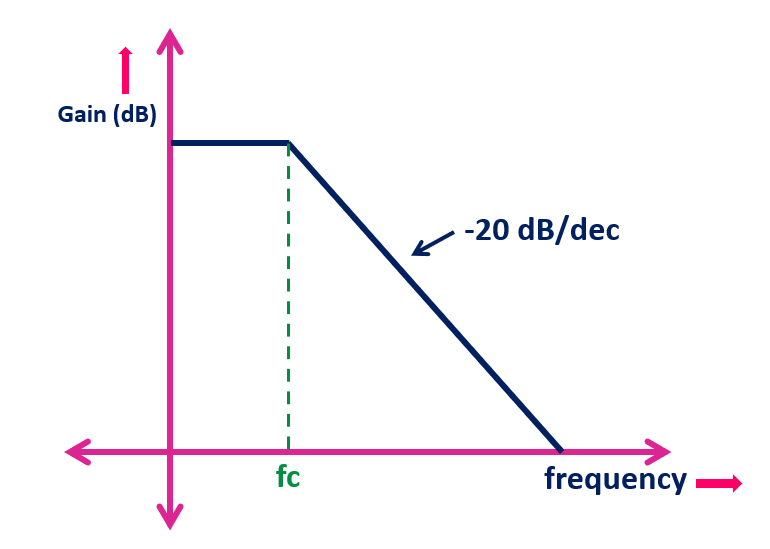

The “constant GBW” assumption

Most internally compensated voltage-feedback op-amps behave like this:

- One dominant pole

- −20 dB/decade roll-off

- Nearly constant GBW

This is an approximation, not a law of nature. Real devices bend the rule.

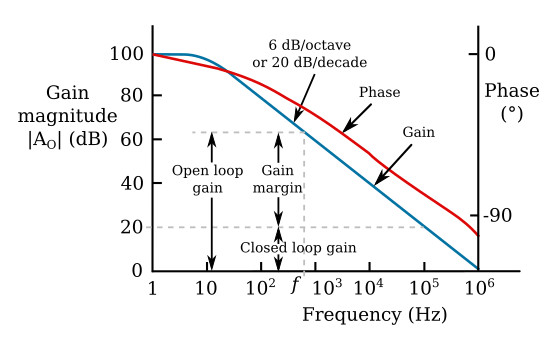

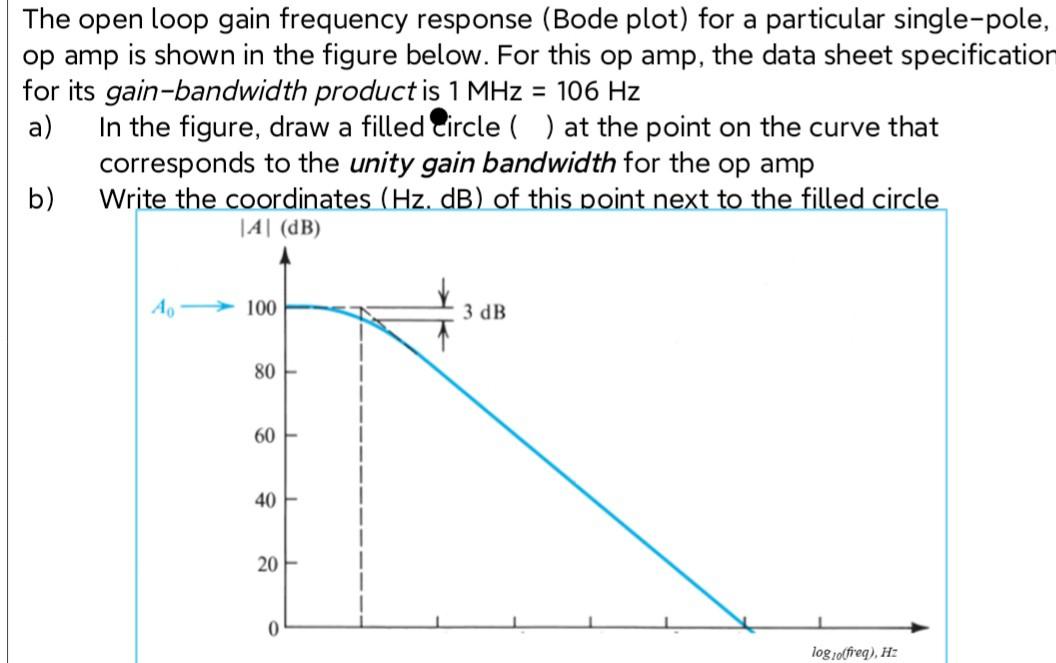

2. How to Visualize GBW in an Op-Amp

The best way to understand GBW is to see it.

Frequency response view

On a Bode plot:

- Open-loop gain starts very high

- Gain falls with frequency

- The point where gain hits 1× (0 dB) defines the unity-gain bandwidth

That frequency is the GBW.

Closed-loop behavior

When you set gain externally:

- The gain line moves down

- The bandwidth shrinks proportionally

Phase matters

Near the GBW limit:

- Phase shift increases

- Group delay rises

- Stability margin shrinks

Key takeaway:

GBW sets the edge where accuracy fades and instability begins.

3. Why GBW Matters in Real-World Applications

Ignoring GBW does not cause subtle problems.

It causes obvious failures.

Signal integrity and accuracy

Insufficient GBW leads to:

- Gain error

- Amplitude droop

- Frequency-dependent distortion

Timing and control loops

In feedback systems:

- Low GBW increases loop delay

- Phase margin collapses

- Oscillation becomes likely

Waveform fidelity

- Sine waves lose amplitude

- Square waves round off

- Fast edges disappear

Certification and reliability

Designs that “almost work” often:

- Fail EMI testing

- Drift over temperature

- Break under tolerance stacking

4. Practical Example: How GBW Limits Your Design

Let’s use a 10 MHz GBW op-amp.

Bandwidth at common gains

| Closed-Loop Gain | Bandwidth |

|---|---|

| 1× | 10 MHz |

| 10× | 1 MHz |

| 100× | 100 kHz |

What this means

If your signal is:

- 500 kHz

- Gain = 20×

You already exceed the GBW limit.

The result:

- Lower gain than expected

- Phase error

- Distortion

When degradation starts

Performance degrades well before the −3 dB point.

Good designs use only 10–20% of the theoretical limit.

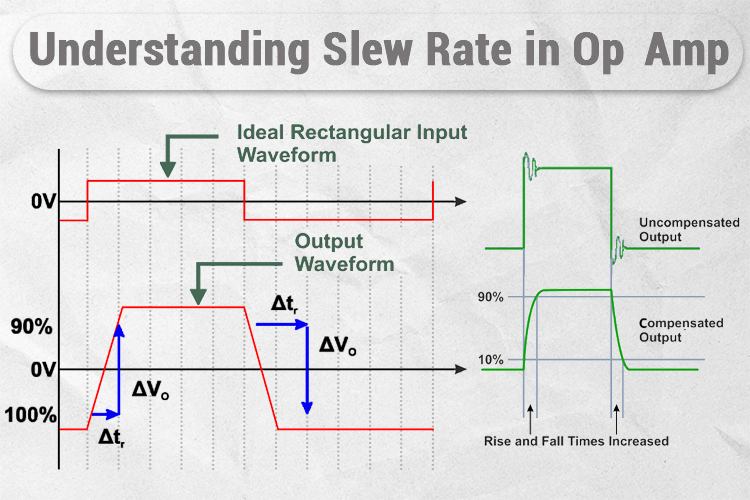

5. GBW vs Slew Rate (SR): Two Different Speed Limits

GBW and slew rate are often confused. They are not the same.

Small-signal vs large-signal

- GBW limits small-signal frequency response

- Slew Rate limits how fast voltage can change

When slew rate dominates

Even with enough GBW:

- Large amplitudes

- High frequencies

Can cause slew-rate distortion.

Rule of thumb

[

\text{Required SR} \ge 2\pi f V_{peak}

]

Common failure

Designers check GBW

…but forget slew rate.

The result: distorted waveforms that simulations never showed.

6. GBW in Non-Ideal and Real Op-Amps

Real op-amps are not single-pole systems.

Multi-pole behavior

Additional poles cause:

- Non-constant GBW

- Faster phase loss

- Reduced stability margin

Why datasheet plots matter

The headline GBW number hides:

- Peaking

- Gain compression

- Phase collapse

Always read:

- Open-loop gain vs frequency

- Phase margin vs load

- Closed-loop bandwidth curves

Stability implications

Higher GBW without proper compensation can:

- Ring

- Oscillate

- Radiate EMI

7. GBW, Stability, and Reliability Considerations

High GBW is powerful—but dangerous.

Phase margin and loop stability

As bandwidth increases:

- Phase margin shrinks

- Noise gain rises

- Layout becomes critical

Failure modes near GBW

- Output ringing

- Bursty oscillation

- Intermittent EMI failures

Long-term risks

Marginal designs:

- Fail temperature cycling

- Drift with aging

- Break during production variation

Too much GBW?

Excess GBW can:

- Increase noise

- Reduce EMI immunity

- Increase cost without benefit

8. GBW Design Rules of Thumb and Selection Strategy

Safe GBW ratios

| Application Type | Recommended GBW |

|---|---|

| General analog | ≥10× signal freq |

| Precision | ≥20× |

| Control loops | ≥30× |

Selection checklist

Before choosing an op-amp:

- Required gain?

- Signal frequency?

- Signal amplitude?

- Load capacitance?

- Temperature range?

Procurement risks

Second-source parts may:

- List same GBW

- Behave very differently

Always qualify behavior, not just numbers.

Summary: How to Use GBW Correctly and Confidently

GBW is not a speed rating.

It is not a quality score.

It is a boundary condition.

What GBW tells you

- Maximum usable bandwidth at a given gain

- Where accuracy begins to degrade

What GBW does not tell you

- Slew-rate performance

- Noise behavior

- Stability margin

- Large-signal fidelity

Final lesson

As electronics pioneer Bob Widlar famously implied through his designs:

Understanding limits is more important than chasing specifications.

Use GBW as a design constraint, not a marketing number.

That is how robust, stable, and reliable op-amp systems are built.