IC Switching Frequency Basics: A Practical Guide for Smarter Design and Sourcing

Switching frequency is one of the most misunderstood—and most powerful—parameters in IC-based power and signal design.

It looks simple. A single number in a datasheet.

Yet it quietly shapes efficiency, heat, size, EMI, cost, and even long-term reliability.

As an old engineering proverb says: “What you don’t tune will eventually cost you.”

Switching frequency is exactly that kind of variable.

This guide explains IC switching frequency in plain language, with real tradeoffs, practical tables, and design-focused insight—so engineers and buyers can make smarter choices.

What Is IC Switching Frequency?

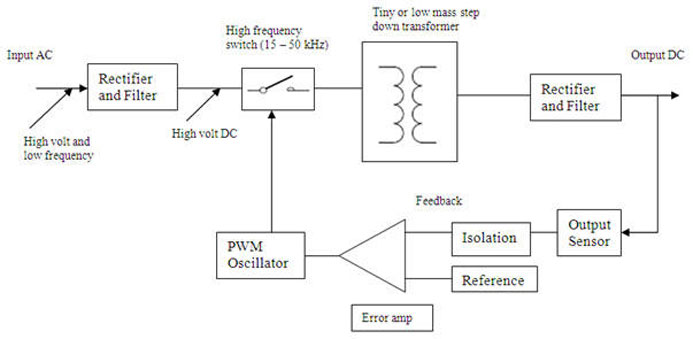

Switching frequency is the rate at which an IC’s internal switch turns on and off.

It is usually expressed in kilohertz (kHz) or megahertz (MHz).

Short sentence. Big impact.

At 500 kHz, the switch toggles 500,000 times per second.

At 2 MHz, it toggles 2 million times per second.

Where switching frequency matters most

Switching frequency is critical in:

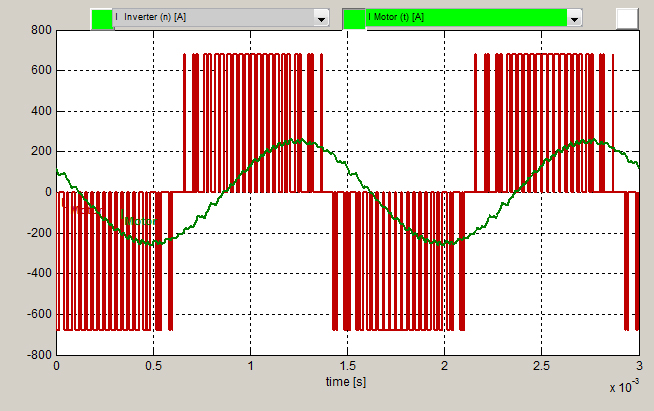

- DC-DC converters and power management ICs

- Motor drivers and LED drivers

- RF and high-speed signal ICs

- Battery-powered and compact systems

If energy is being chopped, stored, or transferred—frequency matters.

Why IC Switching Frequency Matters in Electronic Products

Switching frequency is a system-level decision, not just a chip parameter.

Core impacts

- Efficiency – Too high increases switching losses; too low increases conduction losses

- Heat – Frequency directly affects thermal stress

- Size – Higher frequency enables smaller inductors and capacitors

- Performance – Affects transient response and regulation stability

- EMI – Determines where noise appears in the spectrum

For engineers, it’s a design lever.

For buyers, it affects cost, availability, and reliability.

As Henry Petroski famously noted: “Engineering is about tradeoffs.”

Switching frequency is one of the sharpest ones.

Typical Switching Frequency Ranges by Application

| Application Type | Typical Frequency Range |

|---|---|

| Buck / Boost DC-DC Converters | 200 kHz – 2 MHz |

| High-Density Power Modules | 1 MHz – 5 MHz |

| RF / High-Speed Signal ICs | 10 MHz – 100+ MHz |

| Automotive Power ICs | 300 kHz – 2 MHz |

| Industrial Power Supplies | 100 kHz – 500 kHz |

Lower frequencies dominate legacy and industrial designs.

Higher frequencies enable compact, modern electronics.

There is no “default best” frequency—only a best fit.

Factors That Determine Switching Frequency Limits

Switching frequency is not chosen freely.

It is constrained by physics, silicon, and heat.

Key limiting factors

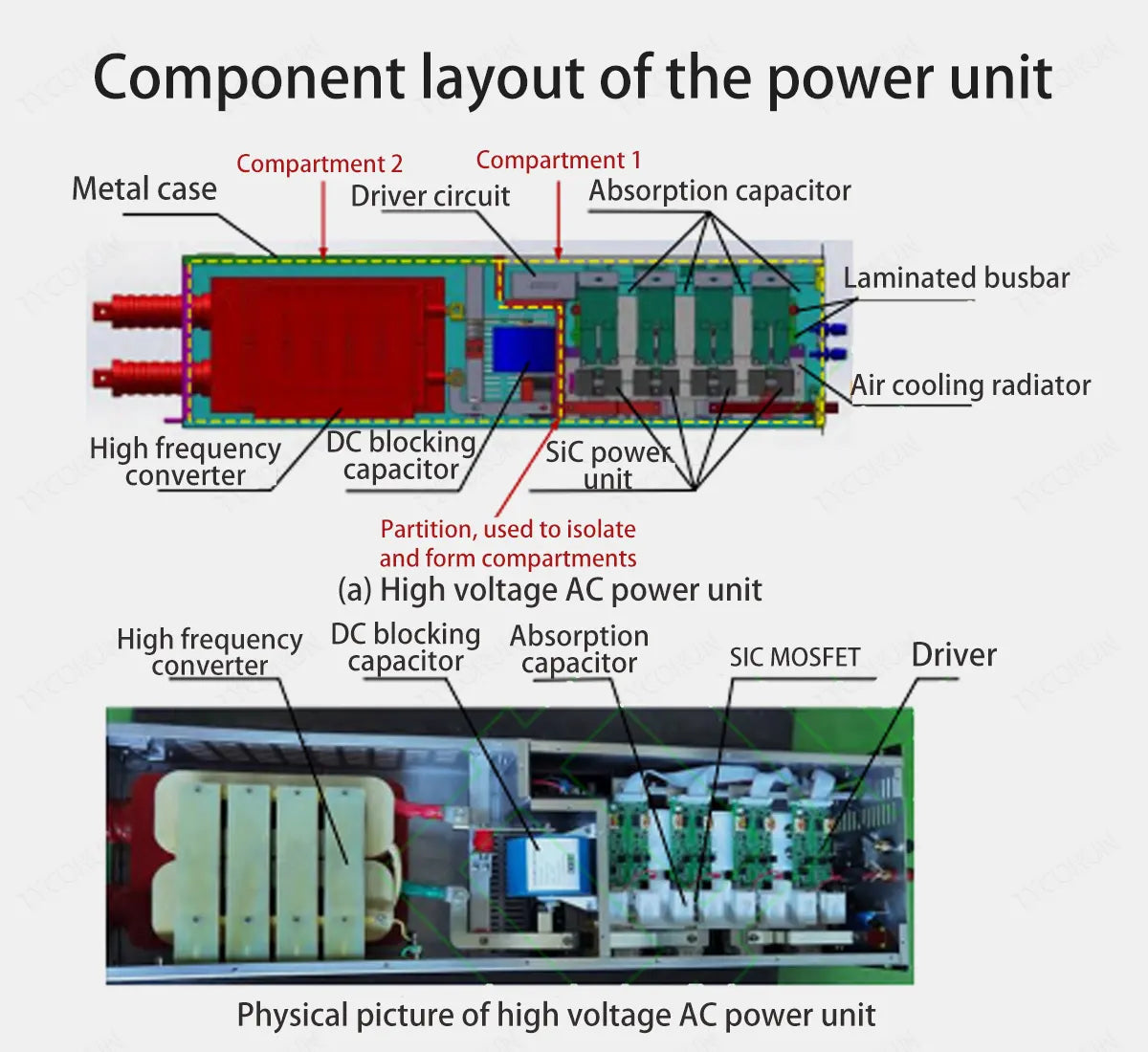

- Semiconductor technology

- CMOS: moderate frequency, low cost

- GaN & SiC: much higher frequency, higher cost

- Internal IC architecture

- Control loop bandwidth

- Gate driver strength

- Switching losses

- Rise/fall time

- Gate charge and parasitics

- Thermal limits

- Junction temperature

- Package dissipation

- Process node

- Smaller nodes switch faster but leak more

Frequency always pushes against losses and temperature.

High vs. Low Switching Frequency: Key Tradeoffs

This is the classic dilemma.

| Parameter | Higher Frequency | Lower Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Passive size | Smaller | Larger |

| Efficiency (high load) | Often lower | Often higher |

| EMI frequency | Higher band | Lower band |

| Transient response | Faster | Slower |

| Thermal stress | Higher | Lower |

| Design margin | Narrower | Wider |

Higher frequency favors compact, fast designs.

Lower frequency favors efficiency, robustness, and longevity.

The smart choice matches product goals, not trends.

Switching Frequency vs. Efficiency Behavio

Efficiency does not scale linearly with frequency.

What really happens

- At low frequency, conduction losses dominate

- At high frequency, switching losses dominate

- Peak efficiency occurs at a sweet spot, not at extremes

Load-dependent behavior

- Light load: Many ICs reduce frequency (pulse skipping or burst mode)

- Full load: Fixed or maximum frequency dominates losses

Modern ICs use:

- Burst mode

- Pulse-skipping

- Frequency foldback

These techniques improve light-load efficiency but complicate EMI analysis.

Switching Frequency, Component Size, and BOM Cost

Frequency directly reshapes the bill of materials.

| Frequency Choice | Inductor Size | Capacitor Size | PCB Area | BOM Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤300 kHz) | Large | Large | Bigger | Lower IC cost |

| Medium (500 kHz–1 MHz) | Medium | Medium | Balanced | Balanced |

| High (≥2 MHz) | Small | Small | Compact | Higher IC cost |

Higher frequency:

- Shrinks magnetics

- Reduces PCB area

- Increases IC complexity and price

Total system cost—not IC cost alone—must be evaluated.

Switching Frequency and EMI / Compliance Reality

Switching frequency defines where noise lives.

EMI truths

- Frequency does not determine EMI magnitude alone

- Layout, rise time, and current loops matter more

- Higher frequency moves noise to harder-to-filter bands

Designers must consider compliance with:

- FCC (consumer & commercial electronics)

- CISPR (industrial and automotive standards)

Practical mitigation tools

- Spread-spectrum frequency modulation

- Synchronization across rails

- Proper LC filtering and shielding

EMI is managed—not eliminated.

How to Choose the Right Switching Frequency

There is no formula.

But there is a process.

Ask these questions

- What efficiency target matters most—light load or full load?

- How much PCB area is available?

- What thermal margin is acceptable?

- Which EMI bands must be avoided?

- Is long-term reliability more important than size?

Strategic alignment

- Consumer electronics favor higher frequency, smaller size

- Industrial and automotive favor lower frequency, stability

- Battery devices need adaptive frequency behavior

A conservative frequency often wins over time.

Final Thoughts: Switching Frequency Is a Design Strategy

Switching frequency is not just a spec.

It is a design philosophy.

Push it higher, and you gain size—but lose margin.

Pull it lower, and you gain efficiency—but lose density.

The best engineers don’t chase the highest number.

They choose the right number.

As the old saying goes: “Good design is invisible—but its consequences are not.”

Choose your switching frequency wisely.